Apocalyptic Thoughts Amid Nature’s Chaos? You Could Be Forgiven www.nytimes.com/2017/09/08/us/hurricane-irma-earthquake-fires.htm

www.nytimes.com/2017/09/08/us/hurricane-irma-earthquake-fires.html

September 8, 2017

CLEWISTON, Fla. — Vicious hurricanes all in a row, one having swamped Houston and another about to buzz through Florida after ripping up the Caribbean.

Wildfires bursting out all over the West after a season of scorching hot temperatures and years of dryness.

And late Thursday night, off the coast of Mexico, a monster of an earthquake.

You could be forgiven for thinking apocalyptic thoughts, like the science fiction writer John Scalzi who, surveying the charred and flooded and shaken landscape, declared that this “sure as hell feels like the End Times are getting in a few dress rehearsals right about now.”

These aren't the End Times, but it sure as hell feels like the End Times are getting in a few dress rehearsals right about now.

— John Scalzi (@scalzi) Sept. 8, 2017

Or the street corner preacher in Harlem overheard earlier this week ranting about Harvey, Irma and Kim Jong Un, in no particular order.

Or the tens of thousands who retweeted this image of golfers playing against a raging inferno of a wildfire in Oregon.

In the pantheon of visual metaphors for America today, this is the money shot. pic.twitter.com/09COuDutBC

— David Simon (@aodespair) Sept. 7, 2017

And just last month darkness descended on the land as the moon erased the sun. Everyone thought the eclipse was awesome, but now we’re not so sure — for all the recent ruin seems deeply, darkly not coincidental.

If you thought that, you would be wrong, of course. As any scientist will tell you, nature doesn’t work that way.

Spates of hurricanes, even major ones, are common in late summer and early fall, the height of hurricane season. Especially destructive hurricanes are not unknown either, and climate change may be making more of them. Irma, in size and strength, is near the top of the charts, but not yet off them and its fury can be explained by scientific principles.

Wildfires have been happening out West for millenniums, though humans have made things worse. Climate change plays a role here, too, plus our desire to live next to nature, not to mention decades of firefighting policies that have made large fires more likely.

And earthquakes — they happen all the time, and the numbers of quakes, from weak to powerful, is unwavering when averaged over time. There is roughly one “great” quake, of magnitude 8 or higher, per year. Mexico was the unlucky winner this time.

But still.

Clearly for a lot of people, science is not enough when the stakes seem so high.

“For so many years, talking about the weather was talking about nothing,” said Terry Tempest Williams, the author and naturalist who is currently a writer in residence at Harvard Divinity School. “Now it really is our survival.”

But how we talk about it is reflective of our worldview – and has been for a long time, said Christiana Zenner Peppard, an associate professor of theology, science and ethics at Fordham University.

“With unexpected cataclysmic weather events, people across time and space have always looked for explanations,” she said.

“The fact is it is attractive to certain segments of the population to look at unforeseen apocalyptic-style events as fitting into a particular kind of narrative,” she added.

While the sense of some gathering apocalypse is not sending people into bunkers, it lingers even in secular minds, if not always consciously.

“We are all much more superstitious than we recognize, and it takes a lot of logical thinking not to believe that this part of the world is not being somehow persecuted,” said George Loewenstein, a professor of economics and psychology at Carnegie Mellon University.

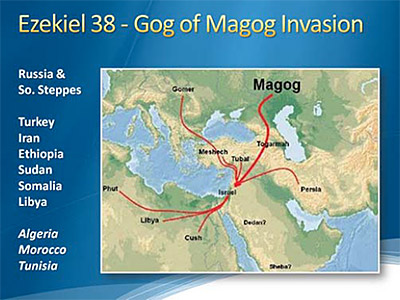

In deeply religious communities, the recent sequence of catastrophic events and threats — terror and nuclear weapon tests, as well as natural disasters — can be understood more easily through prophecy than logic.

Hmmmmm pic.twitter.com/AxJD8YccZg

— Lane Kiffin (@lane_Kiffin) Sept. 8, 2017

Richard Hecht, a professor of religious studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, said that many believers could indeed see this chaotic summer as a sign of the end of times.

“End of times fantasies have been a central part of American religiosity since the beginning, so it shouldn’t be any surprise” if many people sense its approach, Dr. Hecht said. “It’s one thing to believe the ministers’ or preachers’ calculations of the end of days. But now you have objective truths: Charlottesville, the solar eclipse, Hurricane Harvey, the earthquake in Mexico, Hurricane Irma.

“These are events no one can dispute,” he continued. “It’s not the same order of a preacher saying that on September 8, at 10 o’clock, the world will end.”

Ahmed Ragab, a professor of science and religion at Harvard, argues that there is a good reason some people see doom in what’s going on: The pileup of disasters is affecting people.

“Thinking about this series of crises requires that we not only think about the connection to science but also about the effect of these crises on humans,” Dr. Ragab said.

“Natural disasters do not happen in a vacuum,” he added. “The reason we are hearing about them is they are affecting humans, and the structures that we are actually building.”

This is not just aging infrastructure that cannot survive a strong hurricane, or log homes that burn in a fire, but economic structures that leave some people too poor to flee when disaster threatens, Dr. Ragab said.

Dr. Zenner Peppard of Fordham said that no matter what people might think about a confluence of disastrous events, “humans are capable of foreseeing and planning for predictable kinds of outcome — flooding and water scarcity among them.

“To pretend that it’s such a tragedy is to pretend that there’s no social and collective responsibility for the outcome.”