Post by DrSchadenfreude on Jul 27, 2023 14:04:53 GMT -5

How Florida Undermined the “Benefits” of Newly Free Black People

The state’s 1865 constitution sought to preserve the trappings of slavery.

www.motherjones.com/politics/2023/07/slavery-beneficial-skills-florida-ron-desantis-stop-woke-black-codes/

July 27, 2023

Excerpt

"...after emancipation, the former Confederate states crafted new constitutions—later dubbed “Black codes”—that strictly limited the ability of emancipated slaves to apply whatever skills they’d serendipitously acquired while enslaved.

“Like most southern whites, a majority of the citizens of Florida were racists. They generally considered the Negro inferior and criminally inclined; he was untruthful, disposed to steal, and fearfully licentious,” wrote Florida State University historian Joe Richardson in “Florida Black Codes, a 1968 journal article.

The attendees of Florida’s 1865 constitutional convention relied heavily on a three-man committee tasked with recommending provisions “relating to the freedmen,” Richardson wrote. “After praising the institution of slavery and reminding the legislature that it had been destroyed without their concurrence, the committee members recommended legislation which would ‘preserve as many as possible’ of the ‘better’ features of slavery.” State lawmakers took most of their advice, he added.

Florida’s constitution, enacted in 1865, started by proclaiming that all “freemen…have certain inherent and indefeasible rights, among which are those of enjoying and defending life and liberty; of acquiring, possessing and protecting property and reputation, and of pursuing their happiness.” It then went on to stomp on the social and economic rights of Black people.

Political ambition was out of the question: No person shall be a state representative or senator, the document reads, “unless he be a white man.”

In addition, “the testimony of colored persons shall be excluded” from criminal proceedings, except when they pertained to the victimization of a “colored person,” or to their “rights and remedies.” In such cases, “the jury shall judge the credibility of the testimony.”

Also note: “The Jurors of this State shall be white men.”

If a person is convicted of an offense calling for a fine and imprisonment only, the constitution said, “there shall be super-added, as an alternative, the punishment of standing in the pillory for one hour, or whipping, not exceeding thirty-nine stripes on the bare back, or both, at the discretion of the jury.”

“Every able bodied person who has no visible means of living…shall be deemed to be a vagrant.”

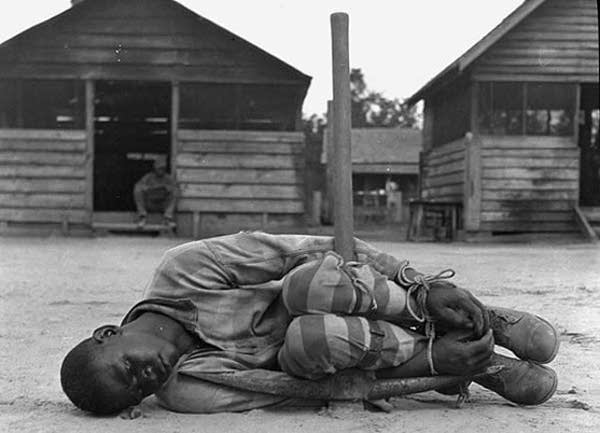

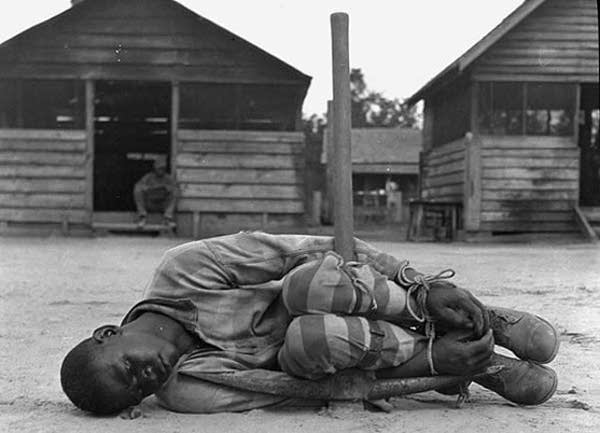

Florida’s Black codes declared that “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall in future exist in this State, except as a punishment for crimes.” This sneaky exception, codified earlier the same year in the 13th Amendment to the US Constitution, would spawn a long and brutal regime of Black convict leasing in the South that Pulitzer-winning author Douglas Blackmon dubbed “Slavery by Another Name.”

The “desire for unpaid or poorly paid labor was widespread” in Florida, historian Joe Richardson noted. And state lawmakers met that desire by criminalizing perceived nuisance behaviors and relying on local officials to enforce the law selectively against Black people. “Every able bodied person who has no visible means of living, and shall not be employed at some labor to support himself or herself, or shall be leading an idle, immoral or profligate course of life, shall be deemed to be a vagrant,” the constitution declared.

A person arrested for vagrancy was “bound in sufficient surety for his or her good behavior and future industry for one year.” If convicted of violating this model-citizen pledge, or if they refused to accept it, the (Black) person faced up to a year of imprisonment or forced labor—or the pillory and/or whipping."

The state’s 1865 constitution sought to preserve the trappings of slavery.

www.motherjones.com/politics/2023/07/slavery-beneficial-skills-florida-ron-desantis-stop-woke-black-codes/

July 27, 2023

Excerpt

"...after emancipation, the former Confederate states crafted new constitutions—later dubbed “Black codes”—that strictly limited the ability of emancipated slaves to apply whatever skills they’d serendipitously acquired while enslaved.

“Like most southern whites, a majority of the citizens of Florida were racists. They generally considered the Negro inferior and criminally inclined; he was untruthful, disposed to steal, and fearfully licentious,” wrote Florida State University historian Joe Richardson in “Florida Black Codes, a 1968 journal article.

The attendees of Florida’s 1865 constitutional convention relied heavily on a three-man committee tasked with recommending provisions “relating to the freedmen,” Richardson wrote. “After praising the institution of slavery and reminding the legislature that it had been destroyed without their concurrence, the committee members recommended legislation which would ‘preserve as many as possible’ of the ‘better’ features of slavery.” State lawmakers took most of their advice, he added.

Florida’s constitution, enacted in 1865, started by proclaiming that all “freemen…have certain inherent and indefeasible rights, among which are those of enjoying and defending life and liberty; of acquiring, possessing and protecting property and reputation, and of pursuing their happiness.” It then went on to stomp on the social and economic rights of Black people.

Political ambition was out of the question: No person shall be a state representative or senator, the document reads, “unless he be a white man.”

In addition, “the testimony of colored persons shall be excluded” from criminal proceedings, except when they pertained to the victimization of a “colored person,” or to their “rights and remedies.” In such cases, “the jury shall judge the credibility of the testimony.”

Also note: “The Jurors of this State shall be white men.”

If a person is convicted of an offense calling for a fine and imprisonment only, the constitution said, “there shall be super-added, as an alternative, the punishment of standing in the pillory for one hour, or whipping, not exceeding thirty-nine stripes on the bare back, or both, at the discretion of the jury.”

“Every able bodied person who has no visible means of living…shall be deemed to be a vagrant.”

Florida’s Black codes declared that “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall in future exist in this State, except as a punishment for crimes.” This sneaky exception, codified earlier the same year in the 13th Amendment to the US Constitution, would spawn a long and brutal regime of Black convict leasing in the South that Pulitzer-winning author Douglas Blackmon dubbed “Slavery by Another Name.”

The “desire for unpaid or poorly paid labor was widespread” in Florida, historian Joe Richardson noted. And state lawmakers met that desire by criminalizing perceived nuisance behaviors and relying on local officials to enforce the law selectively against Black people. “Every able bodied person who has no visible means of living, and shall not be employed at some labor to support himself or herself, or shall be leading an idle, immoral or profligate course of life, shall be deemed to be a vagrant,” the constitution declared.

A person arrested for vagrancy was “bound in sufficient surety for his or her good behavior and future industry for one year.” If convicted of violating this model-citizen pledge, or if they refused to accept it, the (Black) person faced up to a year of imprisonment or forced labor—or the pillory and/or whipping."

................................

................................ ................................

................................